Earlier this week, Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, outlined the steps that ordinary Americans might take to stem the spread of COVID-19, the viral disease causing panic and disruption around the globe.

Households might have to keep patients, along with family members they may have infected, at home. Schools might have to close. Businesses might have to allow workers who can perform their jobs without coming to the workplace to telecommute.

Messonnier, whose agency is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, acknowledged that these measures might involve “unwanted consequences and further disruptions,” including “missed work and loss of income.”

If one of us gets sick, we will have no choice but to keep driving.

Uber/Lyft driver Alvaro Balainez

No kidding. Messonnier outlined the realities that all but guarantee that COVID-9 will spread within the U.S.

A huge proportion of American workers simply don’t have the economic power to stay home, whether to care for family members or even to give themselves a chance to recover from a viral infection in solitude, or the legal right to take off from work without losing their jobs or pay.

Millions of Americans, moreover, don’t have access to healthcare without shouldering significant bills. That will keep many people out of doctors’ offices or even emergency rooms where they might be screened for the novel coronavirus.

Put simply, the consequences of America’s working culture and its fragmented, overpriced healthcare system may hit home in a major way.

About a quarter of all American workers have no right to sick leave, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In service industries — where employees must report to their places of employment to work and are most likely to come in contact with the public — more than half have no sick leave.

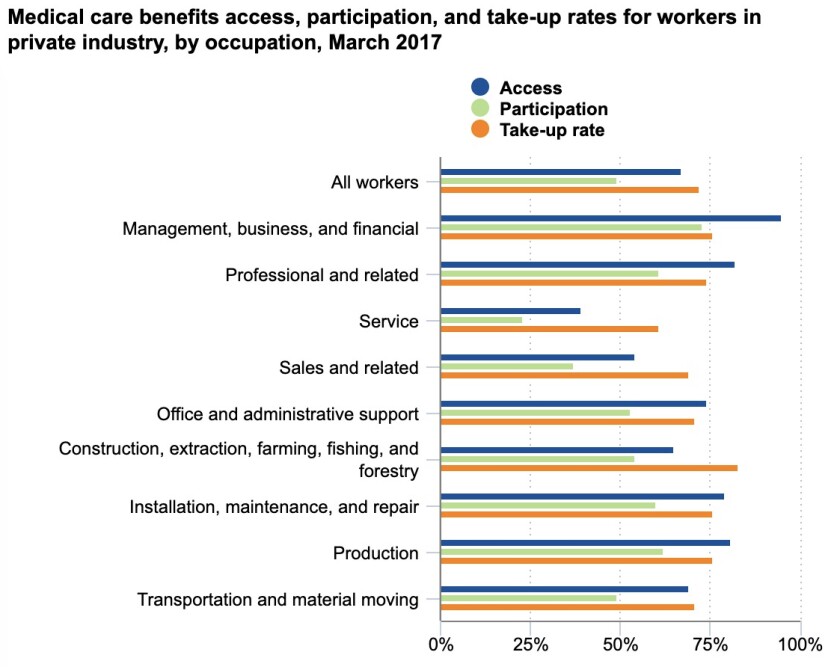

About two-thirds of all workers have access to health benefits at work, but that’s overstating things. Because the cost of premiums can be more than they can afford, only about half of eligible workers actually sign up for coverage. And when they do, many still face daunting deductibles or co-pays that keep them from seeking care.

Fewer than half of all service workers have access to employer healthcare, and fewer than one-fourth can afford to take it. “Take-up rate” refers to the percentage of those offered a plan who accept it.

(Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Those circumstances mean that workers who should stay home are likely to remain on the job, at the expense of their own and others’ health.

“If one of us gets sick, we will have no choice but to keep driving,” says Alvaro Balainez, 33, who has been driving full-time for the ride-hailing services Uber and Lyft for the last six years.

Balainez, who says he earned about $35,000 last year but only about $10,000 after expenses, says that on a Facebook group of thousands of drivers he belongs to, concerns about the effects of a COVID-19 outbreak has become Topic A. “We don’t have medical or savings, because we’re barely making enough to pay our rent or bills,” he told me.

This could hugely intensify the public health crisis caused by COVID-19. The closest analogous case occurred in 2009, when the H1N1 flu virus struck the U.S. An estimated 26 million residents were infected by the virus from September through November that year, the peak months of the pandemic. But an estimated 8 million continued to go to work.

By the following February, public health authorities reckoned that those carriers infected some 7 million co-workers. The problem was especially acute in the private sector, where paid sick leave was relatively rare. “Presenteeism—attending work while ill—among private sector employees without paid sick days may have extended the duration of the outbreak,” a study by Pennsylvania State University concluded. The problem extended to schoolchildren: Those whose parents had access to sick leave stayed home, but those whose parents did not stayed in school, raising the risk of infecting their fellow pupils.

The U.S. hasn’t seemed to have learned the lesson of 2009, since millions of private-sector workers still get no sick leave. Today, about 91% of state and local government workers are eligible for paid sick leave, but only 73% of the privately-employed.

In the private sector, moreover, paid sick leave is a privilege reserved largely to professionals, managers, and the better-paid. It’s available to only about 58% of service workers, less than half of those in the lowest 25% of the income range, and only three in 10 of those in the lowest 10% of wage earners.

Even where sick leave is available in the U.S., typically by state or local ordinance, it’s often unpaid. In Britain, however, workers are entitled to sick pay of at least $120 a week for up to seven months, at their employer’s expense. In France, the government and employers together cover 90% of a worker’s pay for up to 30 days of sick leave, 67% after that.

In China, the epicenter of the developing outbreak, workers are guaranteed 60% to 100% of their salary for up to six months, depending on their seniority, and 40% to 60% for up to six years after that. Those liberal standards may have eased the pain for workers when authorities imposed stringent quarantines in Wuhan province, where the virus is thought to have originated.

In the U.S., no federal law requires paid sick leave. California and nine other states, and Washington, D.C., and some other cities, have enacted mandates, but they’re typically much less generous than the standards overseas. California’s law, which went into effect in 2015, gives workers at least one hour of sick leave for every 30 hours worked, and allows employers to cap the leave at three days per year, though unused time can be carried over to the following year.

The lack of paid time off for workers reflects the dominance of management culture over labor interests in the U.S. over the last century. Business fought back aggressively against government urgings for shorter hours and better pay during the New Deal, for example — and that was in a period when labor rights were on the rise.

At the heart of the Great Depression in 1934, Alfred P. Sloan, then chairman of General Motors, returned from three weeks’ vacation in France to condemn the government position.

“Of course I believe in more leisure for workers,” he said from the wharf. “But we should get it by reduced costs and increased efficiency, not by government edict. We should earn our leisure.”

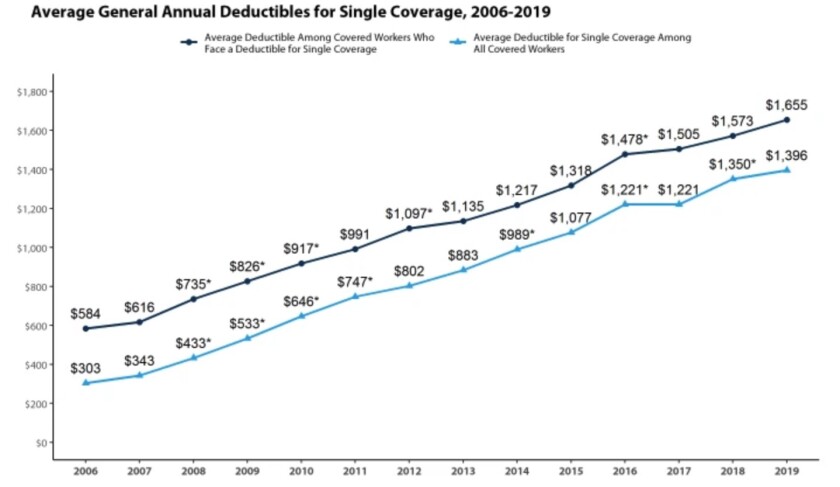

Average deductibles for workers have been rising for years, presenting an obstacle for those who wish to use their health plans.

(Kaiser Family Foundation)

The lack of paid sick leave is only one of the conditions that will hamper efforts to control COVID-19. The other is a healthcare system that either renders millions of residents ineligible for care or prices it so high that even those offered health plans can’t afford to sign up or use them.

A survey conducted jointly in 2019 by The Times and the Kaiser Family Foundation found that four in 10 Americans with employer-sponsored health coverage still had difficulty affording the health plan or treatment. One in four couldn’t afford medical bills before meeting their deductible, and 14% couldn’t afford co-pays for prescriptions.

Of those facing financial obstacles, half had placed their charges on credit cards or used up all or most of their savings to pay medical expenses. Two-thirds had cut spending on food or clothing to pay the bills.

The reason is no secret. The cost of employer health coverage has been rising. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, average deductibles for employer-sponsored single coverage rose to $1,655 in 2019 from $584 in 2006.

That makes health coverage unattainable for low-income workers. That’s the case for Amparo Ramirez, 48, who works in the cold food facility of the airline catering service LSG Sky Chefs at LAX, where she earns the minimum wage of $15.25 an hour, preparing meals for airline passengers. Ramirez says she can’t afford premiums for the company’s health plan to cover herself and her two daughters.

“Even my co-workers who have the coverage say they have to use half their paychecks to get care,” she told me. Instead, she sometimes drives to Tijuana to obtain low-cost treatment or medicines.

Only 33% of the Sky Chefs workers at LAX carry health insurance for themselves and only 10% cover dependents, according to Unite Here Local 11, which represents 900 workers at the company. The union says that nearly two-thirds of respondents to a survey of its members reported having gone to work sick.

Ramirez says she’s been working although she has been suffering from a form of bronchitis for three months. Her employer would grant her up to two days of sick leave, but after that she would need to produce a doctor’s note — something she can’t get because she can’t afford to see a doctor.

Obstacles like these are bound to keep people from seeking treatment, even if they suspect they’ve contracted COVID-19. Government officials haven’t appeared to get the message that the American system itself may be a threat to public health if COVID-19 takes root within our borders. And once it does, the Trump administration doesn’t appear to accept its responsibility to ensure that treatment is widely available.

The administration has spent three years narrowing Americans’ opportunities for affordable healthcare and trying to shrink public health programs such as Medicaid, which could become a bulwark against the virus’ spread if allowed to serve low-income patients without political interference.

Asked at a congressional hearing Wednesday to guarantee that once a vaccine against the virus is developed, it would be available to all, Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, a former pharmaceutical executive, refused.

“We would want to ensure that we worked to make it affordable,” he said, “but we can’t control that price because we need the private sector to invest. Price controls won’t get us there.”

In other words, the administration, for all its rhetoric about protecting Americans from the viral epidemic, will take a hands-off approach once it comes to pass.

source https://betterweightloss.info/hiltzik-u-s-work-and-healthcare-gaps-are-ideal-for-spreading-coronavirus/

No comments:

Post a Comment